“There are vulnerable marine mammals around the world. If these species are also facing an increase in parasitism, that may be an added stress impacting their rate of recovery.”

— Natalie Mastick

Posted originally at nataliemastick.com/blog/

Until last year, my research revolved around whale foraging behavior. I studied the foraging behavior of humpback whales for my masters and spent several summers in the San Juan Islands studying southern resident killer whale behavior in response to shipping noise with Oceans Initiative. When I met Chelsea Wood, a parasite ecologist at the University of Washington, while scoping out PhD advisors it dawned on me that there was a whole other scale of foraging ecology to consider in whales— that of the parasites living within them.

I had worked with sick marine mammals before and assisted on a handful of necropsies at that point. Parasites were relatively commonplace, but generally not the cause of rehabilitation for the sick animals or death for those we necropsied. I had grown accustomed to ignoring parasites and assuming their effects were negligible. But after meeting Chelsea, it was clear that parasites may play a bigger role in animal health and survival than I had given them credit for. I had been studying southern resident killer whales with Oceans Initiative for several years, working on assessing the impacts of a suite of threats to the population. I thought more about the role parasites might play in an endangered species like the southern resident killer whales, whose recovery is inhibited by multiple stressors. For marine mammals that are already facing a multitude of threats, parasites could be an additional burden that might make the difference between a healthy and a sick animal.

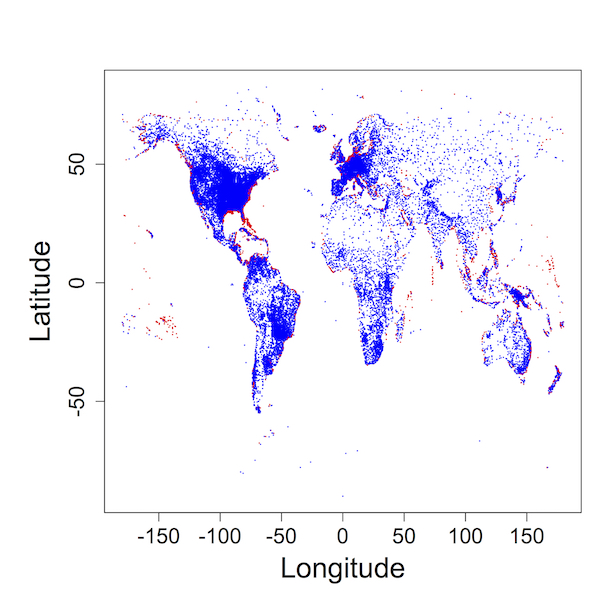

Marine mammal parasites are nearly as widespread as their hosts. Parasitic nematodes of the family Anisakidae, or anisakids, are transmitted to marine mammals through the fish that they eat. Anisakids travel up the food web from copepods to fish or squid until they reach a marine mammal, their definitive host. They inhabit their host’s intestinal tract, reproducing and sending their eggs back into the ocean via their host’s feces to continue the cycle. These parasites can infect a wide range of fish species, leaving many marine mammals vulnerable to infection if their prey harbor anisakids.

There is evidence that anisakids are on the rise around the world. This led me to wonder, are these parasites increasing in the prey that marine mammals eat? And could the most vulnerable marine mammals be at risk to increases in parasitism? This seemed like an important question to address from a recovery and management standpoint. There are vulnerable marine mammals around the world. If these species are also facing an increase in parasitism, that may be an added stress impacting their rate of recovery.

The first chapter of my PhD has focused on answering these questions in some of the most at-risk species— those listed as threatened or endangered in the Endangered Species Act and the IUCN Red List. My lab-mate Evan Fiorenza recently completed a major meta-analysis of the publications on anisakid prevalence over the last 60 years. I compared the ranges and diet species of all IUCN listed species and ESA listed populations, resulting in 14 populations that overlapped with this meta-analysis dataset, ranging 30 years. I also subset the data to look at the species with the most data to see if there was a trend in any of the most well-represented diet species, grouped by the mammal that eats them.

As I am still actively analyzing the data, it is too soon to say whether there has been a change in anisakid abundance in the prey that endangered marine mammals are eating. That being said, I am excited to be presenting my preliminary data and analyses at the World Marine Mammal Conference in Barcelona this week. With any luck, I will be able to talk to some of the experts on these endangered marine mammals to gather more information about their diets to improve the resolution of my study. When I return, I plan to work on increasing the scope of my study to include species listed under Canada’s Species At Risk Act (SARA), and working with the experts at Oceans Initiative to improve range estimates of these species. But for now, I am excited to soak in new information more from the world’s marine mammalogists over the next week.