When ships strike whales, the whale generally loses. People must wonder why scientists treat this issue like it’s some great mystery that’s difficult to quantify and even more difficult to solve. After all, hitting a large whale must be like hitting a moose with your car. Right? So fixing the problem must be as easy as searching the shipping lanes for marine roadkill, and making shippers slow down.

In fact, assessing the extent of ship strike mortality is incredibly challenging. Sure, vessel operators may underreport whale strikes, but in fairness, with very large, fast ships, collisions may go entirely unnoticed. A typical cruise ship may weigh 50,000 tonnes. A typical fin whale may weigh 50 tonnes. Yes, that’s a lot of whale, but it could be analogous to hitting a 2kg animal with a 2,000 kg SUV. Except that the ship strike can happen in a lurching, heaving sea, with the ship moving and whale surfacing and diving in three dimensions. And when whales die, whether from human or natural causes, only a trivial fraction of carcasses are recovered. To us, it’s a wonder that this issue is reported as frequently as it is, given all the odds against detecting the problem in the first place.

Fortunately for the whales, this issue is receiving a lot of scientific and management attention. Off the east coast of the US, scientists have built a convincing case that the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale population cannot withstand the death of even one individual annually from ship strikes, so tremendous bilateral efforts have been made to separate ships from whales in important habitats in both the US and Canada. Recently, regulators have started issuing speeding tickets for mariners who violate the rules designed to protect the whales.

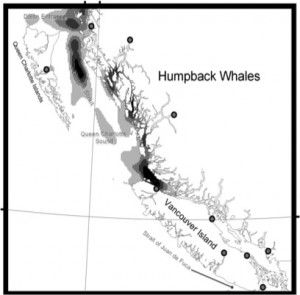

In 2010, we partnered with Dr Patrick O’Hara (Environment Canada) to conduct a risk assessment to identify where ship strikes may be an issue for fin, humpback and killer whales in BC. A risk assessment involves two main components: (a) trying to estimate the likelihood of a thing (usually bad) occurring; and (b) predicting the consequences if it does. Put simply, we mapped where ships and whales are likely to overlap.

This overlap analysis actually tells us three things:

1. oil spill risk: Shipping intensity seems like a good proxy to use for oil spill risk. The probability of an oil spill happening is low, but if it happens, it can be catastrophic to individuals and populations.

2. ship strike: again, the probability of it happening is low, but it can be fatal. And if it happens often enough, it can be damaging to populations. Our work is showing that fin whales in BC cannot tolerate the removal of more than a few individuals per year. Given the occasional, high-profile examples of ship strikes involving fin whales worldwide, we wonder how much of an underestimate these reports represent.

3. chronic ocean noise: high noise levels are a sure thing in a shipping lane, and we’re just beginning to quantify the effects on marine mammal habitats, individuals and populations. Our colleagues are documenting similar effects of noise on non-mammalian wildlife like squid and fish. So, we believe that even if a ship doesn’t strike a whale, this “overlap analysis” can still tell us where important whale habitats are likely to be degraded by chronic ocean noise. Our work has shown that repeated disturbance by boats can disrupt the feeding behaviour of killer whales, and our new research (with Cornell University’s Bioacoustics Research Program and the Sea Mammal Research Unit at the University of St Andrews) is modelling how much acoustic space whales lose from shipping noise.