“Parasitism may play a role in the recovery of at-risk marine mammals, but without digging in and figuring out if this is a new problem or status quo, we won’t know.”

— Natalie Mastick

Posted originally at nataliemastick.com/blog/

There are indents on my nose, my hair smells faintly of ethanol, and I am actively working on realigning my spine after several hours hunched over a microscope. I have just wrapped up a fish dissection, but not a normal fish dissection of a fresh or even thawed fish. This fish was caught in 1985. Once captured, it was fixed in formalin and then stored in ethanol, living in a jar in the Burke Museum’s fish collection at the University of Washington for the last 35 years. This dissection is a small piece of the Wood lab’s effort to reconstruct the past of Puget Sound, and the parasites that lived in it. Each fish preserved contains a snapshot of what parasites infected it when it was caught and subsequently stored in ethanol, to live on a shelf for eternity. By dissecting the species commonly caught in Puget Sound and stored over the past century (that’s right, 100 year-old fish!) we are able to see how parasite diversity has changed in the region.

This has important implications for the fish that these parasites infect. Some of the parasite species found in fish use that fish as their definitive host; they’ll live in that fish for the rest of their lives. Other species, however, use the fish as a stepping stone–or intermediate host–to get to their ideal definitive hosts. These parasites wait until their intermediate host gets eaten, hopefully by a definitive host that they can infect for the rest of their lives. The parasites found in the fish represent the transferable parasites that were inhabiting the environment at that time, available to be eaten by a definitive host.

A group of these parasites are parasitic nematodes (worms) of the family Anisakidae, or anisakids, which I discussed in my blog post “Anisakid risk to endangered marine mammals.” These nematodes have multiple life stages, in which they depend on different hosts. Their first host, or primary host, is a copepod, which then gets eaten by a small fish or squid. In this second host, the nematode encysts in the muscle and waits to get eaten by the next biggest animal, hopefully a marine mammal (a whale, dolphin, seal, sea otter, or sea lion). Unfortuantely for the worm, from there it gets eaten by another fish. But evolution prepared them for this! Anisakids can keep getting eaten by fish and encysting them until they finally reach a marine mammal. Then, once they finally reach a warm-blooded host, they inhabit the stomach or intestine and reproduce. Those eggs are then sent out into the marine environment through the host’s feces, where they can get eaten by a copepod and the whole life cycle can begin again.

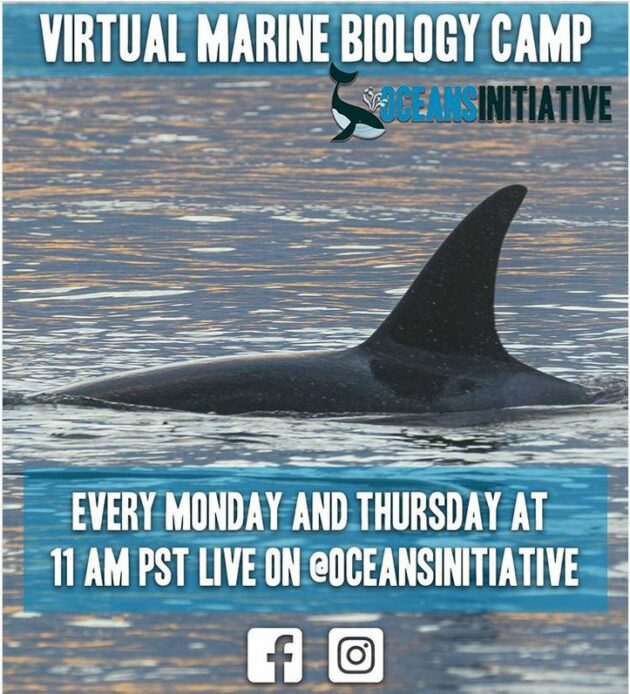

Aniskaids might play a bigger role in marine mammal health than previously thought. Once in the intestinal tract of a marine mammal, anisakids absorb nutrients from the host, taking up energy that would otherwise be used by the host alone. At larger burdens, large amounts of energy can be taken from the host, effectively acting as an energy sink. The whale or seal needs to eat more to account for this energy lost to its parasitic stowaways. But for at-risk or endangered species like the southern resident killer whale, which is already nutritionally stressed, parasitism by these nematodes may represent an additional stressor inhibiting the recovery of the species by acting in concert with other stressors.

In the lab today I was dissecting herring. Herring are an important forage fish in the Pacific Northwest. They form large schools and can be found in open ocean as well as bays. Herring are eaten by humans, fish, and birds, and they also make up a large part of the diet of some marine mammals, including whales, seals, sea lions, and porpoises. They form a foundation of the food web, so that the parasites that they harbor can continue on to a marine mammal, even if they are not consumed by one directly. By assessing how the abundance of anisakid nematodes has changed in herring and other fish, both small and large, that are common prey to marine mammals, I am uncovering how the risk to anisakid infection has changed locally over the past century.

While we are still in the dissection stages and not the analysis quite yet, I think we may see an increase in anisakid abundance. Marine mammals are key to the spread of anisakids in the marine environment, and surprisingly enough some marine mammals in this area have been increasing in number since protections were put in place in the 1970s (think of the skyrocketing populations of sea lions and harbor seals in the area). With more definitive hosts shedding eggs into the environment, the likelihood of infection of fish and subsequently of other mammals increases. I expect that this will be evident through the historical record we’re currently examining.

It is important to determine what parasite abundance in the ecosystem was like in the past because it provides context for what we see today. A component of my research is assessing how parasitized marine mammals in the area are now, and if parasites are likely impacting the health of marine mammals more than they were in the past. If we don’t know what the past was like, we can’t tell if marine mammals today are any worse off now than they were before, especially the at-risk ones like the endangered southern resident killer whale. If at-risk species are facing a more significant threat from parasites today than they were in the past, then those threats could be incorporated into their management. Parasitism may play a role in the recovery of at-risk marine mammals, but without digging in and figuring out if this is a new problem or status quo, we won’t know.