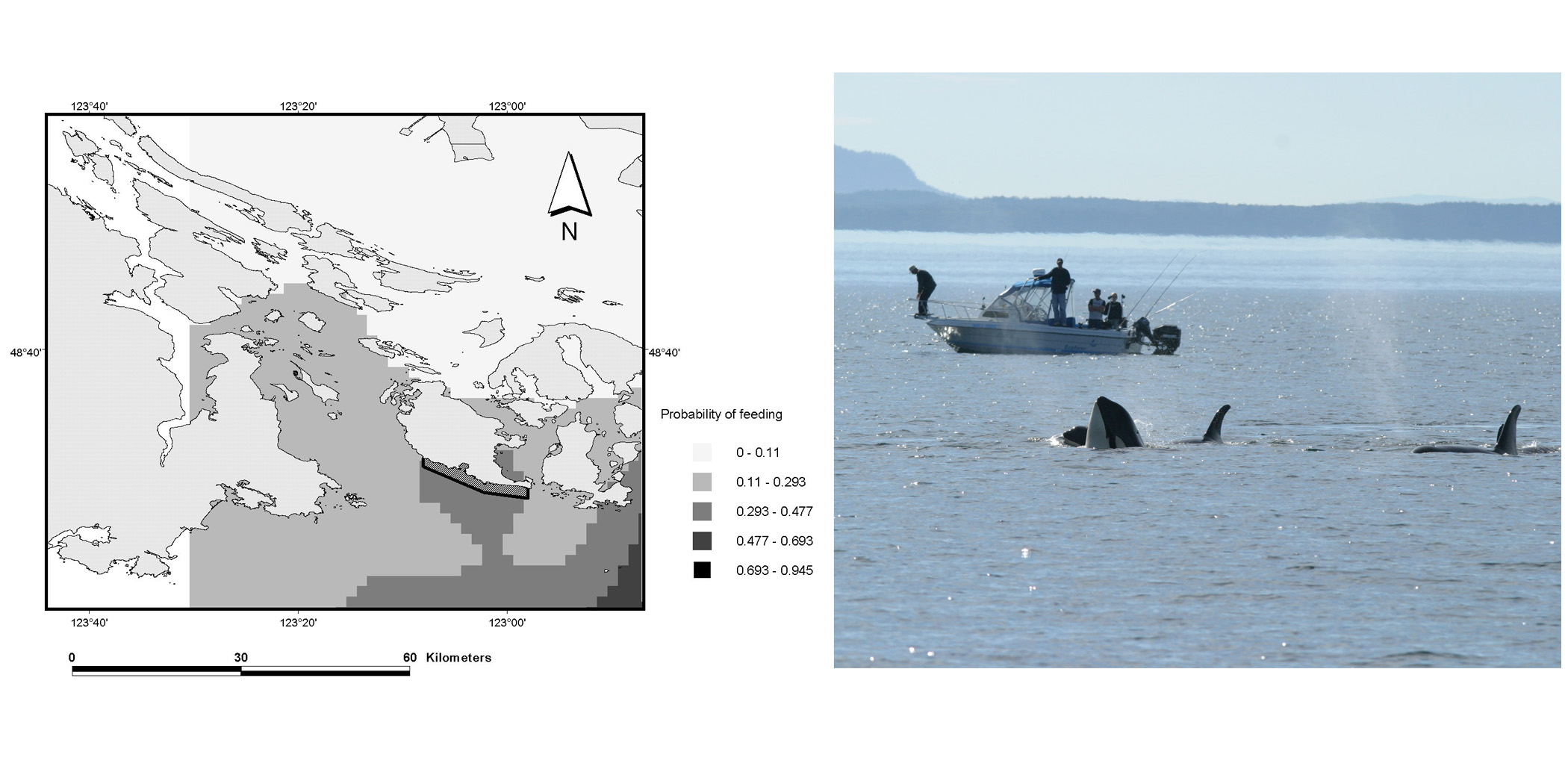

We recently published a paper reporting ocean noise levels in important whale habitats along the BC coast. At the same time, we released an animation that outlined the key concepts. Our research showed that the most important habitats for killer whales were the noisiest; important habitats for humpback whales were comparatively quiet.

We thought you might like to hear for yourself what those sites sound like. Don’t worry. We won’t make you listen to all 10,000 hours of recordings, but our co-authors (Dimitri Ponirakis and Chris Clark) at Cornell University’s Bioacoustics Research Program distilled some of the results into this nifty PowerPoint slide. It’s a big file (22MB), but it lets you see and hear what Haro Strait and Douglas Channel sound like.

The neatest part of Dimitri’s work is that there was a windstorm partway through this period. You can hear the wind on the recordings made off Kitimat (Douglas Channel), but the same wind noise cannot be heard in Haro Strait over the background noise from ships. We still have a lot of work to do to understand what these noise levels might mean to whales and fish in terms of ecological effects, but we thought you might like to see and hear some of the recordings. Please let us know what you think.

[slideonline id=5854]