At New Year’s, we all make resolutions about diet. But we’ve got nothing on Pacific humpback whales, which are currently on their mating and calving grounds in Hawaii and Mexico. During this time, they go weeks or months without eating at all. BC waters provide important habitat for these highly migratory animals. When they’re here in summer, they only have a few months to put on all the fat reserves they need to migrate over 4000km (each way) across the ocean, calve, mate, nurse their calves and return to BC to start the cycle all over again. From our perspective, this creates a sense of responsibility for Canadian resource management: human activities that degrade the quality of feeding habitat in BC waters carries consequences that affect the whales throughout the rest of their range.

WE LOVE THE BBC SERIES, “NATURE’S GREAT EVENTS“.

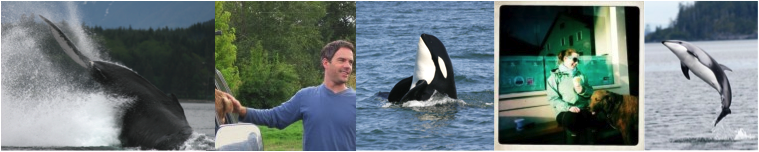

Humpback whales eat a lot, and they accomplish all of this without teeth. How do they do that? An incredibly gifted filmmaker, Shane Moore shot this extraordinary footage for the BBC that shows the northeast Pacific ecosystem much better than we ever could describe in words (although Sir David Attenborough comes a close second to the whales themselves). [Please note: BBC put this link on youtube, but they’ve also put some other amazing footage on their site, which we encourage you to see.] Enough lead-in. Check out this frenzy of seabirds, herring and whales:

MEANWHILE, BACK AT THE RANCH…

Of course, not all marine mammals migrate. Some, like the Pacific white-sided dolphins we study, have been seen in our study area every month of the year. Dolphins, including the killer whale (the largest member of the dolphin family) do not fast over the winter months. Instead, they eat like we do — constantly. And dolphins and killer whales both have teeth, and big brains, to help them come up with clever ways to find their prey.

The following video shows dolphins and killer whales hunting. You might want to watch this on your own before deciding whether it’s appropriate for younger viewers. [Note. We collect our photographs and video under a research permit. We learn a lot through photo-ID, but we are obviously not filmmakers.]

[vsw id=”14224604″ source=”vimeo” width=”600″ height=”400″ autoplay=”no”]

Listen. Everybody’s gotta eat. The whales aren’t doing this because they hate dolphins. They’re doing this because, like dolphins, us and all organisms that can’t feed themselves through photosynthesis, whales need to eat to survive. Our colleague, Jackie Hildering, recently witnessed a similar event.

A lot of our work aims to estimate abundance of whales, dolphins and other top predators, because we want to see ecosystem-based fishery management practices that ensure that nutritional needs of marine wildlife are taken into consideration when setting fishing quotas. But lately, we’re growing concerned about the potential for underwater noise to mask the ability of a whale or dolphin to find its prey or detect when predators are nearby. Going back to Shane Moore’s tremendous BBC footage, a frenzy like that must make some noise that a humpback whale could hear and use to locate a school of fish. OK. We’re guessing at that — it hasn’t been proven scientifically (although this is a research question we’d love to take on). Our colleagues have shown convincingly that killer whales use sound to find and locate their prey, so it’s not rocket science to guess that human-caused noise can disrupt that sensitive acoustic system.

OK. Maybe we shouldn’t make this all about human activities. Maybe you should forget the text, watch that BBC footage again and just appreciate, as we do, how neat these animals are.