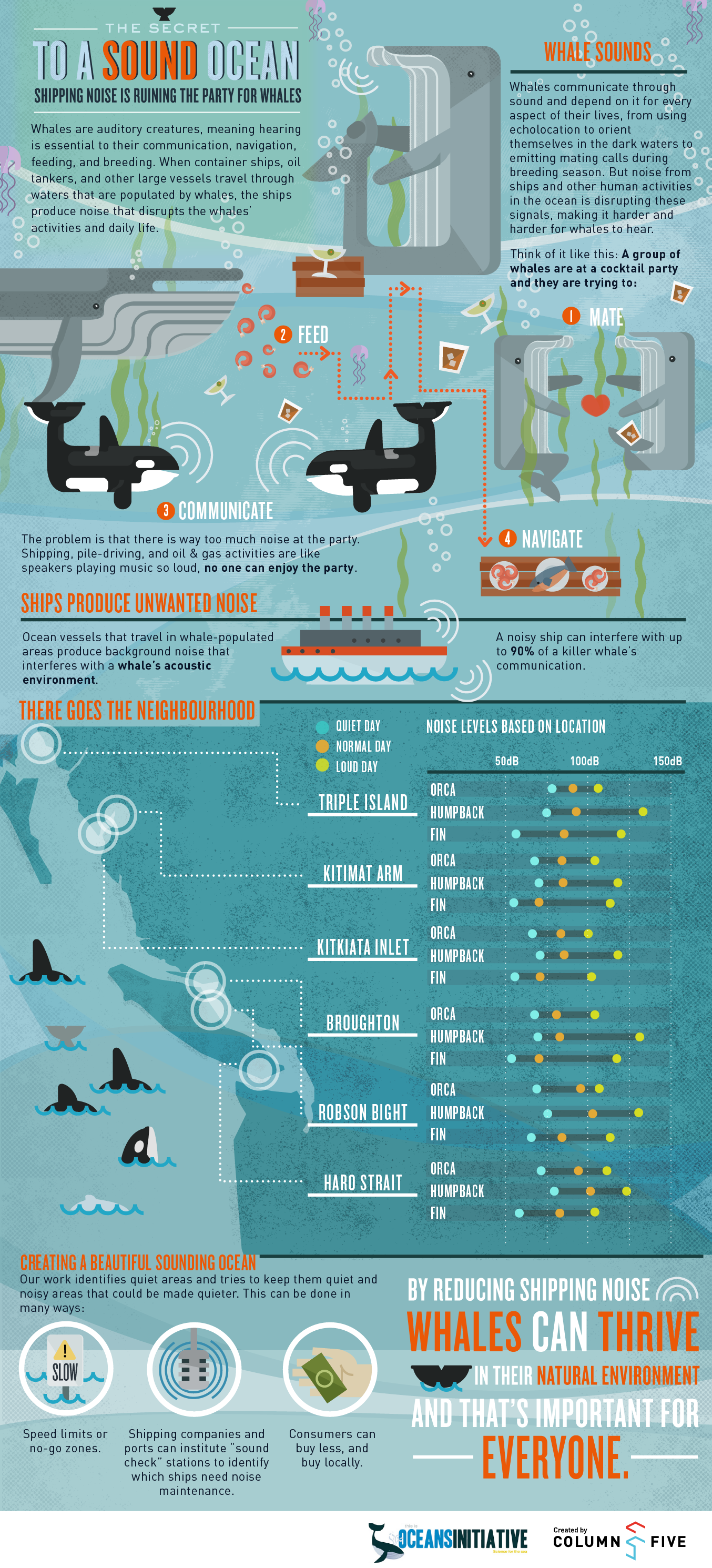

The Secret to a Sound Ocean

Oceans Initiative is a team of scientists on a mission to protect whales, dolphins and their habitat. To celebrate World Oceans Day, we’re releasing the main findings from our Ocean Noise project. Our clever friends at Column Five Media have helped us turn our cutting-edge acoustics research with Cornell University’s Bioacoustics Research Program into a simple, visual story. Please feel free to download the infographic, or share our page with your friends.

We’ve been studying marine mammals since 1995, and much of the work we do involves estimating how many marine mammals are found in British Columbia waters, where they live, how human activities impact their lives, and how much food they need to thrive.

But whale habitat is more than physical space and food to eat.

“The places in which these animals live are defined not only in terms of space, but in terms of sound – they live in an acoustic world and depend on that world for survival,” says Dr. Christopher Clark from the Cornell Lab’s Bioacoustics Research Program, who has been listening in on the whales to get a better understanding of how noise impacts their acoustic habitat. “Imagine living in a village where you can’t see each other or where you’re going. Instead, everyone relies on sounds and calls to go about your lives and to maintain the social network. What happens to your world as the smog of noise gets to the point where you cannot hear each other?”

We love partnering with smart, talented people to multiply our impact. In 2008, we partnered with Dr Christopher Clark and Dimitri Ponirakis at Cornell University’s Bioacoustics Research Program to find out how ocean noise levels in British Columbia measure up to the rest of the world. We wanted to find out whether the whales in BC have a relatively quiet ocean or if ocean noise levels are high enough to challenge the whales’ ability to hear each other and find food.

With the help of a few visionary funders and a very long list of generous friends (THANK YOU!) who helped us in the field, we used Cornell’s cutting-edge hardware (specialized underwater microphones) to record shipping noise and whale calls in strategic sites along the BC coast in 2008, 2008 & 2010. The hydrophone recorders sit on the seabed for weeks or months, recording all ocean sounds (human and natural), then we navigate back to where the hydrophones were dropped, play a signal to them and the device pops up to the surface with a record of everything it heard during the deployment.

Once we retrieve the hydrophones, Dimitri Ponirakis works his magic in the Cornell lab, and turns thousands of hours of recordings, terabytes of data, into some results that we can use to quantify how noisy or quiet whale habitats are. We then asked the visionary team at Column 5 Media to help turn our decibels and decimals into a delightfully appealing infographic that communicates our results.

The Secret to a Sound Ocean infographic shows typical noise levels in three frequency bands. Think of it this way: the three bands represent what the noise levels may sound like to a killer whale (a soprano), a humpback whale (a tenor) and a fin whale (a bass). What we’re finding is that some of the most important areas for killer whales (e.g., Robson Bight & Haro Strait) happen to be among the noisiest sites we sampled. And some of the areas that are most important for humpback whales are fairly quiet (Caamano Sound, Kitkiata Inlet), but could get a lot noisier given the number of industrial developments planned for the area. Our data for this important area are unique, and we are glad that our funders helped us collect essential baseline recordings while the area is still relatively quiet.

Our plans for this work is to put this all into a framework that allows us to answer the So What? question. We’re able to model how much acoustic habitat these different whale species lose in sites with different noise levels. Rob’s Fulbright Chair position explored the ocean noise issue from a policy perspective. Now his Marie Curie fellowship at the University of St Andrews allows him to build mathematical models to explore how chronic ocean noise could affect the dynamics of fin, humpback and killer whale populations.

The thing we love most about this issue is that it is a relatively solvable problem that lends itself to creative solutions to make life quieter for marine wildlife. Our current work identifies whether we can reduce noise levels by asking ships to slow down or avoid certain areas altogether. We’re identifying whether some areas are so quiet that they should be recognized as national treasures: acoustic refuges that we try to manage so they stay quiet. Our mission is to identify noisy areas and to help make them quieter; and to identify quiet areas and to try to keep them quiet.

If you’d like to help our efforts do that, please spread the word. Please share this page, subscribe to our newsletter, or follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest or our Aeroplan Beyond Miles donation page. Thanks again to everyone who has helped us do this work, and Happy World Oceans Day!!!!!

If you have any questions, please contact us:

-Rob Williams & Erin Ashe