This is a big week for the planet. Earth Day and the one-year anniversary of the BP/Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. It will take years to assess the damage from the Gulf spill economically, societally and ecologically. A recent paper in Conservation Letters led by Oceans Initiative’s Dr Rob Williams with the help of many co-authors, suggests that the dead dolphins washing up on the beach are really just the tip of the iceberg. The team evaluated historic carcass recovery rates in two ways. One indicated that there could be as many as 50 dolphins that were scavenged, drifted offshore or sank to the bottom of the ocean for every dolphin carcass recovered on the beaches. The other method yielded an even scarier ratio of 250:1.

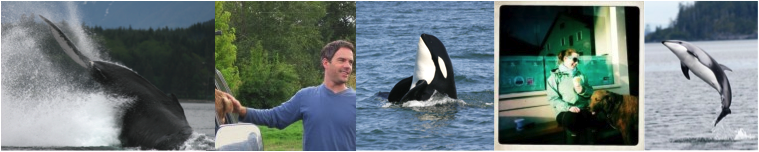

Dead whales and dolphins on beaches represent only the damage we can see. Killer whale biologist and director of the North Gulf Oceanic Society, Craig Matkin, notes that a genetically distinct pod of killer whales, the AT1pod, exposed to oil from the Exxon Valdez oil spill, have yet to reproduce 22 years later. Since no calves have been born, the unique killer whale pod will be lost. However grim the statistics, scientists are able to make these calculations thanks to years of careful research on whale and dolphin populations. Closer to home, imagine how warped our perception of killer whale populations in BC and Washington would be if all the information we had available came from the occasional carcass that washes ashore, instead of conducting annual counts of the entire population, which is what our colleagues at Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Center for Whale Research do. There is simply no substitute for the hands-on, hard work of long-term monitoring of cetacean populations.

But many cetacean populations are still under the radar. You may be surprised to find that for many whale and dolphin species, we still lack basic information on how many there are and how healthy the populations are. In 2004, we partnered with Raincoast Conservation to design and conduct systematic surveys to estimate abundance of 6 cetacean species in BC, and we’ve seen first-hand that it is possible to contribute important baseline science while working on a modest budget.

At Oceans Initiative, our aim is to identify data gaps and make it a priority to fill the ones we can afford to (and are most qualified) to fill. Earth Day prompts us to reflect on the contribution we are making to marine research and conservation, but our goal, every day, is to identify modest contributions that we can make to improve the quantity and quality of science available to make decisions that sustain the BC marine environment.

Our recent dolphin ‘spring fling’ {AKA Dolphin-Palooza 2011} is a good example. With 10 days and a lot of help from our friends and neighbours, we collected gigabytes of photo-identification and acoustic data on Pacific white-sided dolphins in BC, at the extreme south end of the Great Bear Rainforest. Because we are building on Alexandra Morton’s 20 years’ worth of meticulous photographs and observations, we expect that soon we will have a good estimate of abundance, survival and a glimpse into Pacific white-sided dolphin population structure. These important pieces of information form the basis on which sound management decisions can be made. The kind of baseline information we are collecting is essential, whether we are dealing with day-to-day conservation and management decisions or (heaven forbid) assessing damage and supporting recovery if a catastrophe on the scale of the BP oil spill should ever occur in Pacific Northwest waters. The science we do is not the most glamourous kind of field work, but it is necessary. And we love what we do.