I woke up this morning and decided that everyone gets twelve wishes today! Ta-da! Here are ours.

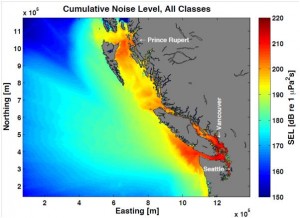

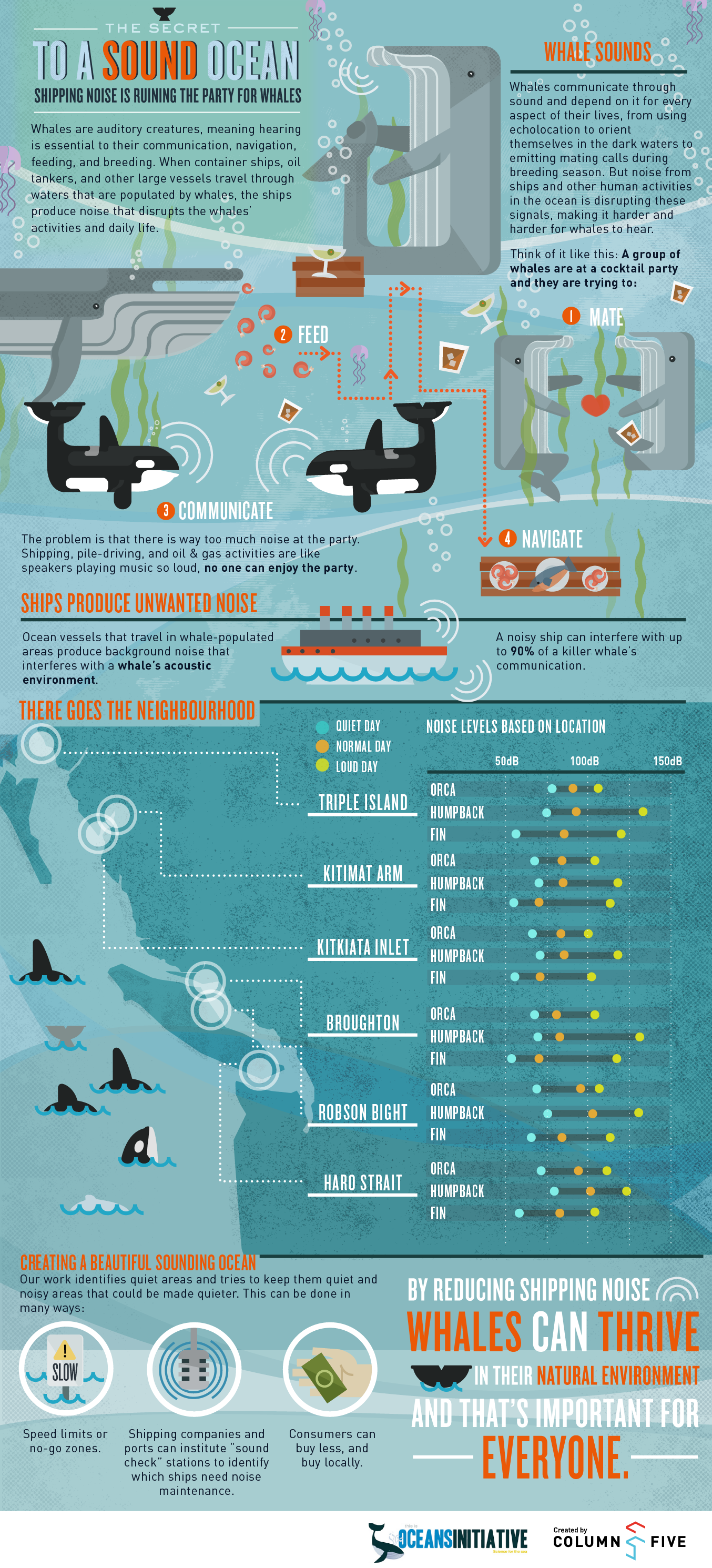

1. Quiet oceans for whales, dolphins and all marine life. You can help make this a reality. Please vote here to support our Quiet Oceans Campaign. It’s easy to vote and you’re welcome to vote once per day!

2. A plastic-free ocean. Help make this one come true by bringing your own bag to the grocery store. As the City of Vancouver says, “Create Memories, Not Garbage” by buying experiences, not gifts, this holiday season. The best way to reduce plastic waste in the ocean is to stop buying things we don’t need.

3. Be an effective voice for ocean conservation in 2013. You can help us achieve our goal by spreading the word about the work we do. We’d like to get to 1000 likes on Facebook in the next 3 months.

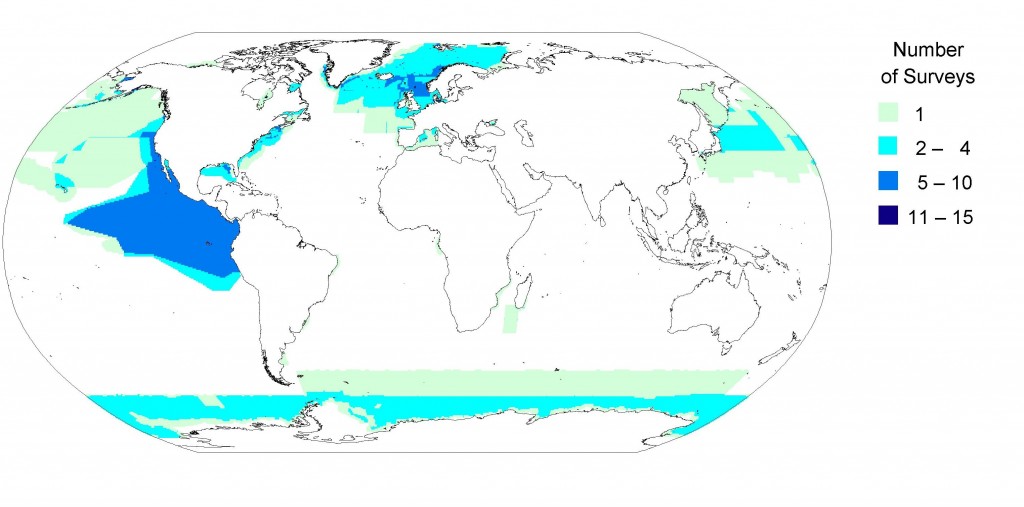

4. Reduce bycatch in fishing gear and marine plastics. Here are our priority regions in BC to reduce marine plastics and their impacts on marine mammals.

5. Subscribe to our newsletter Scroll up near the top of our page to “Get the Ocean in your Inbox”. You’ll be glad you did!

6. Reduce the risk of oil spill. The Deepwater Horizon incident was a huge wake-up call to everyone in the ocean conservation community. Our work showed that every dead dolphin recovered on the beach probably translated to 50-250 deaths that went undetected at sea. In 2013, we’re keen to draw attention to “silent spills” – we’re trying to understand what happens when marine life comes into contact with small oil spills that happen everyday during routine operations when transporting oil by sea. Keep in touch for our new findings.

7. Sign up to become a monthly donor to Oceans Initiative. We hate to ask. We know that everyone is asking you to fund a lot of great causes. But the reality is that our charitable organization can’t function without your financial support. Please consider making a one-time or monthly donation.

8. A new ocean etiquette. This isn’t rocket science. Being a good ocean neighbour is no different than being a good neighbour on land. Don’t litter. Recycle. Keep the noise down when you’re having a party. Pick up your dog poop. Cover your mouth when you cough (i.e., don’t transmit diseases into the ocean through unsafe aquaculture practices).

9. More support for research and conservation for animals like Pacific white-sided dolphins that are currently under the conservation radar, but may need our help. This is a pet peeve of ours. The ocean is facing multiple threats, and we need to set priorities when spending scarce conservation funding. But the current model isn’t working. Too often, we wait for a conservation problem to become a crisis, with funding thrown at the problem in hopes of reversing declines. Instead, we’d like to see a calmer approach, where species are monitored routinely, and potential problems are identified before they become catastrophic.

10. Keep it cool and save the polar ice caps. Everyone loves polar bears and penguins, especially at this time of year. Reduce your dependence on fossil fuels. It feels like a tall order, but we each can make progress in even small ways. We travel a lot to do science (including in the Antarctic), but also to see our science used in making smart decisions to protect the ocean. In fact, we rely on our charitable pooling account with Aeroplan to keep our field costs low. But we’ve recently discovered Aeroplan’s partner programs to offset carbon. We’ve switched to video conference whenever we can, but when we have to travel, we try to offset the carbon costs.

11. For you to become our next Twitter follower. It’s a fantastic spot to engage in conversation. Hope to see you there.

12. Our final wish is for you to connect and engage in ocean conservation in a way that speaks to you. For us, it’s sitting on our deck at our field site, listening to the sounds of whales and dolphins breathing as they swim by. For our land-locked friends, it’s listening to the songs of whales online. What works for you? How do you connect to the ocean? What is your wish for the ocean?

Wishing you all the best for 2013!

-Erin & Rob