Rob and his colleagues published a neat new paper today in the open access journal, PLOS ONE. The paper, led by Dr Kristin Kaschner at the University of Freiburg, examined >1100 estimates of the abundance of whales, dolphins and porpoises reported in more than 400 surveys conducted worldwide between 1975 and 2005.

It is hard to convey how boring science can be sometimes.

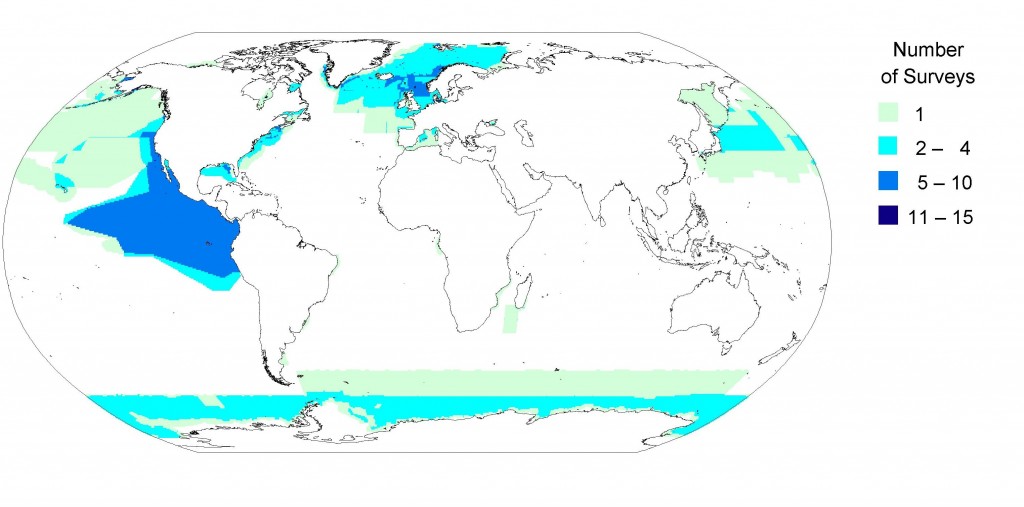

During the research, the team digitized thousands of maps, so you don’t have to. Seriously. Kristin made the data for the map (above) available for download, in case you ever want to do a global analysis of where people have and haven’t surveyed for whales. Here’s what was learned about the global patchiness of whale and dolphin research. Overall, only 25% of the world’s ocean surface has been surveyed at all, while only 6% has been covered well enough to offer any hope of detecting trends in population size. Other findings included:

- The vast majority of surveying effort has taken place in waters under the jurisdiction of wealthy, northern hemisphere countries like the US, Canada and Europe.

- Southern hemisphere regions are underrepresented, except the Antarctic, where the International Whaling Commission leads surveys to estimate abundance of the Antarctic minke whale, which is subject to scientific whaling by Japan.

- Few surveys have taken place in high-seas waters beyond national jurisdiction. This hinders global initiatives to implement high-seas marine protected areas that reflect the habitat needs of whales and dolphins.

- The level of survey effort conducted in the eastern tropical Pacific may look excessive but is actually at the low end of what is needed to detect population trends.

- The main focus for surveying populations was in tuna fishing regions due to the market for “dolphin-friendly” tuna, with more surveys in the eastern tropic Pacific Ocean than in the rest of world combined.

Our ability to protect cetaceans from threats such as military sonar, seismic surveys (for offshore oil exploration), oil spills or bycatch in fisheries hinges on good information, and this latest research indicates a lack of baseline information to evaluate threats across the vast majority of the world’s oceans. As international efforts are underway to protect global biodiversity, the researchers conclude there is an urgent need to develop new methods to fill in data gaps which can in turn improve marine conservation efforts.

Here are some quotes from the authors:

Dr Nicola Quick, co-author and honorary research fellow from the University of St Andrews, commented: “One of the primary motivations for our research was to know where whales might be most vulnerable to the use of military sonar or seismic surveys to find oil under the seabed. The enormous data gaps we found in our study remind us that we still have a lot of work to do to predict whether vulnerable species might be using the waters that have never been surveyed. We recommend international coordination of surveys to share resources to fill in these gaps.”

When looking at the coverage in the eastern tropical Pacific, Kristin noted that “the rest of the world has a lot of catching up to do if we want to know if whale populations are recovering from historic whaling or bycatch in fisheries. The issue of data gaps pervades every issue in marine planning, from fisheries management to marine protected areas. Because of the strict science needs of whaling, the information available on whales and dolphins may paint an optimistic picture of marine science. Knowledge gaps are almost certainly worse for deep-sea invertebrates, sharks or marine viruses.”

Oceans Initiative co-founder, Dr Rob Williams (who is also a Researcher in the Sea Mammal Research Unit at the University of St Andrews) added: “One of the most important management and conservation decisions we make is how to allocate scarce funding for research. As we aim to protect marine biodiversity on a global scale, we need to ensure that our scientific advice reflects the fact that the vast majority of the world ocean has never been surveyed in a comprehensive way. If we ignore that, our advice is biased toward coastal waters of wealthy countries, and that is unjust.”