- Whale you be my Valentine? I dolphinately will! Illustration by Leafeon via Quid Pro Quo on Tumblr

Love prompts us to do brave, romantic and sometimes foolish things. To paraphrase Elizabeth Barrett-Browning, today we’re asking ourselves: How do I love thee, Ocean? Let me count the ways. We came up with 5. On Valentine’s Day this year, here are a five healthy, sane ways to show your love for the ocean.

“They do not love that do not show their love”

Shakespeare, from Two Gentleman of Verona

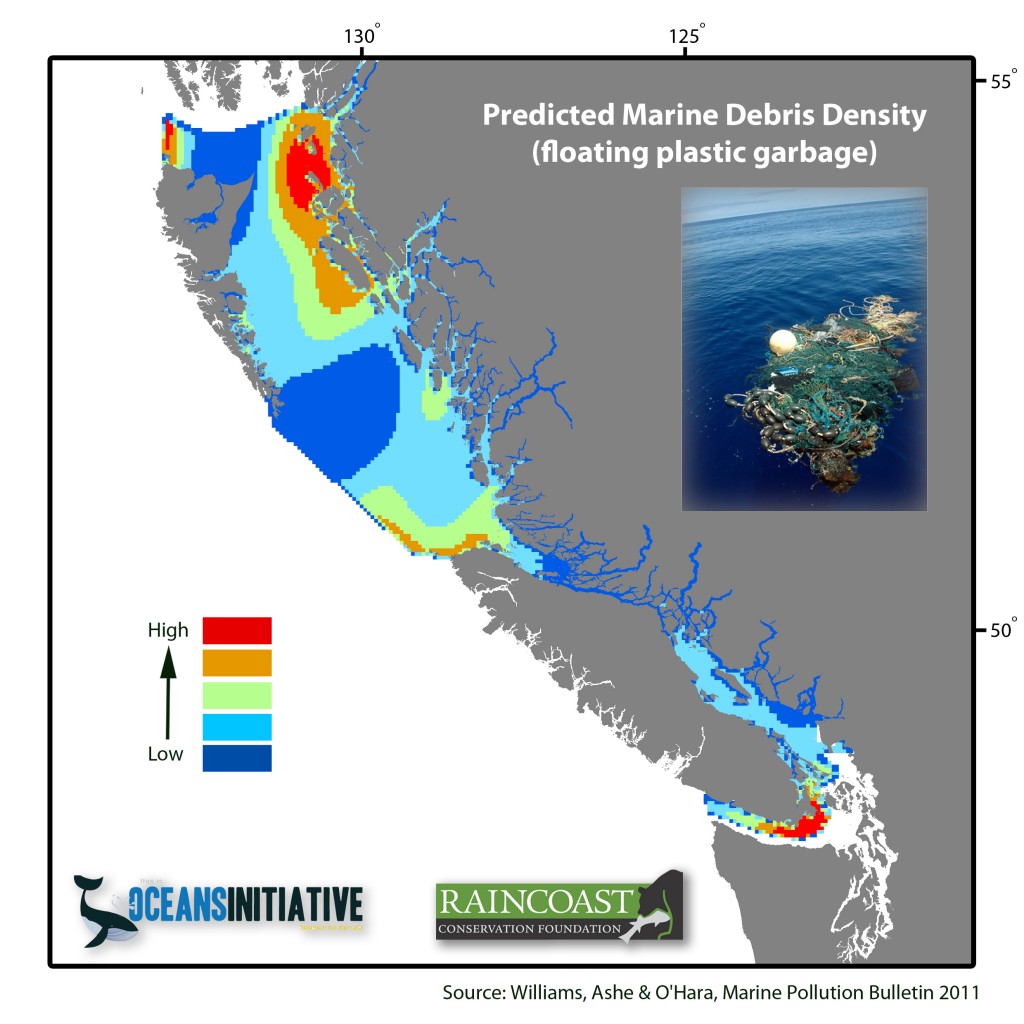

1. Say No to plastics: Marine wildlife accidentally eat and ingest plastics in the ocean, which blocks their stomachs and can cause them to starve. Alternatively, they can get tangled in plastic, which causes them to suffer and suffocate. Either way, it is a huge problem. What can you do?

♥ Use re-useable grocery and shopping bags. More and more cities and small towns are banning plastic bags. Be ahead of the curve and pack a Chico bag or other tote everywhere you go.

♥ Sip your water from sleek, BPA-free water bottles (we love these from Kleen Kanteen) or other re-usable bottle.

♥ Straws suck! Consider going straw free when indulging in your next cocktail (it will cut down on pesky mouth wrinkles). If you’re married to straws, channel your inner Nacho Figueras by using these Oprah-approved stainless steel straws.

2. Eat organic and local: The killer whales we study in the Pacific Northwest are some of the most contaminated marine mammals on the planet. No wonder they are endangered! Toxins from pesticides, antibiotics, and fertilizers used in conventional farming practices eventually find their way into our oceans, into the fish the we and the whales eat and eventually into our bodies where they cause harm. Luckily, you can help by:

♥ Buy organic whenever you can. If organic is not an option, stay away from the Environmental Working Group’s Dirty Dozen and focus on the Clean Fifteen.

♥ Shop at your local farmer’s markets (find yours here) and choosing minimally packaged foods when you shop! While in Scotland, we love going to our local farm shop where we actually see the fields where our food grows!

♥ Dine out at restaurants that include local and organic menu items. Places like Chipotle are relatively inexpensive, and check out their extraordinary commercial on factory farming.

3. Sustainable Seafood: Bycatch in fishing nets poses one of the largest threats to the survival of whales and dolphins on the planet. Each day, thousands of dolphins drown in fishing nets. There are standards, but they vary worldwide, which is why it is important to make informed decisions. At home in the Pacific Northwest, our research has shown that harbour porpoise may be at risk from bycatch in gillnet fisheries in the Salish Sea, and this warrants additional research. Porpoise caught in hook-and-line fisheries (e.g., trolling) are unlikely to cause much marine mammal bycatch.

♥ Choose sustainable seafood with a free guide from the Vancouver Aquarium or US regional guides available for free from the Monterey Bay Aquarium

♥ Choose wild salmon, never farmed salmon

4. Buy less stuff and reduce impacts of global shipping: Noise in the ocean has increased in some areas ten-fold over the last few decades. Why? More than 90% of the things we buy in North America are shipped from overseas, using massive container ships that produce a lot of noise underwater. The ocean soundscape is now dominated by the noise of these distant ships. This is bad news for whales, dolphins, fish and other marine life that depend on sound to communicate, find mates and food. Think about this tonight while you’re trying to hear your Valentine’s sweet nothings over dinner in a crowded restaurant. How can you help?

♥ Buy locally made products whenever you can or join Patagonia’s Common Threads Initiative

♥ Buy gifts on Etsy

♥ Make your own gifts! There are thousands of amazing DIY project ideas on Pinterest

♥ Check out our Quiet Ocean Campaign. We’re working hard to keep quiet places quiet for whales and dolphins.

5. Share the love:

♥ Tweet about this post or like it on Facebook by clicking on the sidebar.

♥ Leave a comment on our website to share more ideas for showing your ocean love.

♥ Subscribe to our newsletter to stay updated on ocean issues by entering your email address in the box in the upper right corner of this page.

♥ Make a tax-deductible donation to support our research, conservation and education initiatives to protect whales, dolphins, sharks and other marine life. Or, donate frequent-flyer points to Aeroplan’s Charitable Pooling Account for Oceans Initiative. This helps us cut the cost of doing the work we do. Thanks for your support! We wish you and your loved ones a very Happy Valentine’s Day!